‘All those theories about Brazil being a country of mixing, that’s a lie’

Financial Times magazine, March 28 2014

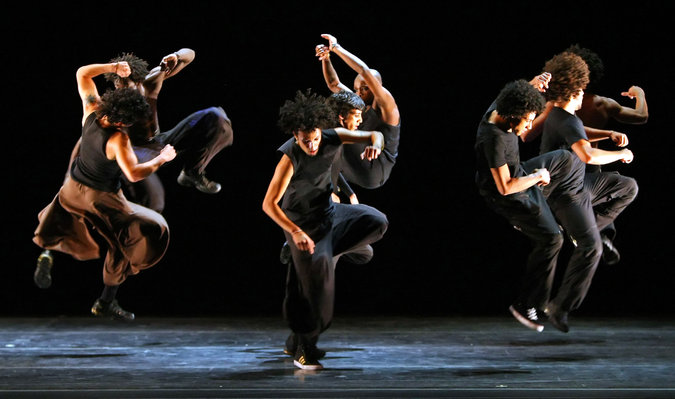

All dance is about the body, how it looks, how it moves, how it connects with others on stage. But for Sonia Destri Lie, artistic director of Companhia Urbana de Dança, a company of eight men and one woman from the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, her dancers’ bodies are also a source of the stories the company tells in its work.

“When you look at Feijão,” she says, gesturing to one of her dancers, “his body is his identity. Through his body you can see his father, his mother, his grandfather, Africa, the periphery … He is black, Brazilian and has lived the life he has lived – and that it is the reason he dances the way he does.”

Destri founded Companhia Urbana nine years ago, to bring the three roots of Brazilian culture – indigenous, European and African – together in contemporary dance. She had no preconceptions about the kind of dancers she would recruit. “When they came to the company, they had very little formal dance experience. What was important for me was whether or not they had a body that was ready to dance,” she says.

She initially thought that she would be the source of the company’s artistic direction but that soon changed: “I realised that their movements were much more beautiful than mine and that the mix of all of us together could be a very interesting journey.”

Destri started as a dancer herself. She trained with Pina Bausch, Alwin Nikolais and Twyla Tharp and, in the 1990s, returned to teach contemporary and Brazilian jazz dance at the Tanztheater in Wuppertal. During this time she developed an interest in the dance emerging around hip hop, not only in Europe but also, she discovered on her return to Rio de Janeiro, in the favelas of her home town.

However, what started as a project to support talented dancers from the favelas soon became a political one too. Companhia Urbana unabashedly deals with issues of race and class that many in Brazil would rather ignore. “Brazil is a country full of prejudice, full of racism,” Destri says. “All those theories about it being a country of mixing – samba, Carnival, gringos – that’s a lie.” She gestures towards her dancers. “If I ask them to go outside and get a taxi, the taxi doesn’t stop, so I have to call a taxi for them. And then, when the taxi comes, the driver won’t take them. And this is in 2014.”

Last year, for the first time, the company received funding from the Brazilian government – enough for six months’ work – and this has crystallised the company’s dreams for the future. “I want to grow old with this company,” Destri says. “But after a while I want them to be able to look after another company here themselves, a young Companhia Urbana. There are already two excellent choreographers here – they don’t know it, but they are. And at some point they will be making pieces themselves. I believe so much in the work, so much in them, that it has to work out.” She looks over to her dancers and tears come to her eyes. “There has to be no possibility that it doesn’t work out.”